Young soldiers in the Israeli War of Independence in 1948: Shimshon Ofer, who spent his childhood until 1938 in Germany, discovered his Haganah Unit - and himself - in this picture by the famous photographer Robert Capa. Photo: Robert Capa © ICP / Magnum / Ag.Focus

"Documented for eternity"

How Shimshon Ofer, who grew up in Bad Mergentheim, discovered himself on a legendary photograph of Robert Capa from the Israeli War of Independence.

by Meinrad Heck

In May 1948, the legendary war photographer Robert Capa took a photo of young soldiers in the Israeli War of Independence. Long before, nine-year-old Siegfried Hirschberg and his family had left their home town of Bad Mergentheim to escape the Nazis. As Shimshon Ofer he had begun a new life in Tel Aviv. Decades later, he discovered his army unit - and himself - by chance on Capa's famous picture. The story of this discovery began with a smile...

Many of the young men in the photo would not survive the following days. It was Sunday 23rd May 1948. In the week before David Ben-Gurion had proclaimed the State of Israel in the Tel Aviv Museum. Five Arab armies attacked that very night, and a few days later the young men in Robert Capa's photo were forced into one of the bloodiest battles of the Israeli war of independence. It went down in history books as the Battle of Latrun.

Latrun was an old police fortress halfway between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. It was in Arab hands, the road to Jerusalem was within reach of Arab rifles and cannons. With 200,000 Jews in the besieged city almost cut off from the supply of food and the outside world. Ben Gurion decided to take this key fortress "under all circumstances.

Years later this should become good material for the Hollywood film industry and many others. Countless directors, authors and historians would make opulent feature films or write books, essays and novels. But before this history could be written, like Robert Capa's photography, people like Shimshon Ofer had to experience it first and above all survive.

He had left the city of his childhood in 1938. As Siegfried Hirschberg he had lived with his brother Arno and his parents in a house in Wettgasse within sight of the synagogue. The last thing he had seen of Bad Mergentheim on March 20, 1938 was the station. The Hirschbergs and their sons had taken a train to Marseille, France, boarded a passenger steamer and arrived in Palestine.

"That was not an escape," he remembers today, but an emigration. The Nazis had established their race laws, the mob in the streets shouted "Don't buy from Jews". It was about time to leave. In 1938 there was still this small window of time in which emigration had been possible. Thus Siegfried Hirschberg had begun a new life under his New Hebrew name Shimshon Ofer.

His grandparents had stayed in Germany. They had lived in Berlin and had been deported by the Nazis to the concentration camp Theresienstadt. Once more mail had come to the children and grandchildren. Once more they had written "Everything is good". But nothing was good. Nothing at all. Shimshon Ofer never heard of "grandpa and grandma" again.

The fortress

And now, in May 1948, he was just 19 years old and a member of the Haganah, formerly an underground army and after the declaration of independence the regular defense army of young Israel. He was on his way to this fortress Latrun, passing some observers, passing Robert Capa without noticing him. They marched towards the horizon, two young men still looked back over their shoulders and one of them smiled. The others left traces in the sand, they had no photographer legends in their minds but were thinking what they would face in Latrun. Many of them who had survived the Holocaust did not have long to live anymore But that one smile would become important again in a few decades.

Fatal error

In the strategically important fortress, their Haganah commanders at best waited for a few Arab militiamen who were contemptuously called "Irregular" at the time during the attack the following night. But in a few hours this would turn out to be a fatal error with fatal consequences. The attack was delayed and did not begin under the cover of darkness, but just before sunrise

Not a few scattered irregulars were waiting in the fortress, but a highly equipped unit of the so-called Arab Legion with the most modern weapons. Shimshon Ofer and his fellow fighters did not have the slightest chance. Their only option to take cover was a few trees or tufts of grass. Most of them died in the hail of bullets from machine guns or from the impact of grenades. Those who could still walk, retreated, took wounded, threw themselves on the ground, when the grenades hit, buried their head under their hands, waited a few seconds, picked themselves up, ran again, made it to the next hill out of sight and perhaps felt safe for a short time - then came the Chamsin.

Chamsin was - and still is - a weather phenomenon, a burning hot and dry desert wind from the interior. Temperatures usually rise to well over 40 degrees. The young men of the Haganah were ill-prepared. They had no canteens and without water during the chamsin you could feel every nerve in the body drying up by the minute. Those who survived the night and did not die of thirst the following day, those who could still drag themselfes from hill to hill, threw away at the end everything what he could no longer carry and tore himself in the hellish blazing heat all clothes from the body except for the trousers. Shimshon survived the hail of bullets and the Chamsin. He made it "completely groggy" into a kibbutz, dragged himself to a water tank, opened a pipe hanging upside down, drank and showered and was "like out of his senses".

They had not conquered Latrun, and they would not succeed in doing so even after several attempts in the following months until the ceasefire. Jerusalem succeeded instead with a trick. At the same time of the unsuccessful attacks, they dug and hammered out of nowhere in a remote valley out of sight of Arab troops within a few weeks a new makeshift road into the mountain slopes, up to Jerusalem. The legendary "Burma Road".

The Journalist

Jerusalem was saved. The war went to end with a ceasefire. At least for now, until the next ones followed. Shimshon Ofer was no longer a soldier, he was a journalist. He wrote reports for the left-liberal newspaper "Al Hamishmar", which meant "the daily watchman". The title was the program. He observed the following wars as a military correspondent, witnessing the ceasefire agreement after the 1973 Jom Kippur War, when the crucial documents were signed in tents at km 101 on the road to Cairo. He had observed it from the outside, because "they did not let us in".

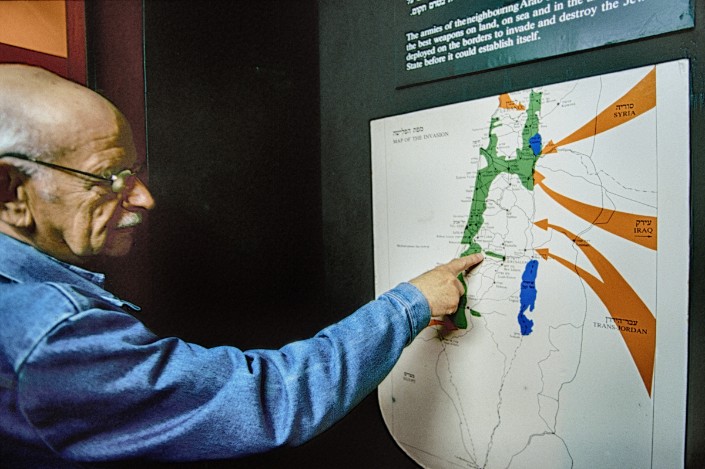

Shimshon Ofer in Tel Aviv with a historical map of the 1948 War of Independence. Red arrows show the attacks of Arab Countries, green the Jewish territories. Ofer points to the place where Capa's famous picture was taken. Photo: Meinrad Heck

Blinded

When he wrote about power and the powerful, he did what all good journalists should do: be there, but don´t belong to it. In 1976, he published a book on the state of Israeli society at that time, which has attracted attention to this day. It had the English subtitle "Blinded by the top" and it described how public opinion threatened to be blinded and manipulated "by the top" with the help of journalists. He emphasized that journalism must not be the extended arm of the government and in Israel, which is constantly threatened from outside, the duty of journalists was not to strengthen the morale of the population. Journalists have to ask questions to the powerful, especially uncomfortable questions.

In 1983, former Jewish fellow citizens who had been found and invited by a circle of friends from Bad Mergentheim all over the world, visited the city of their childhood for the first time again. Shimshon Ofer wrote in his later report published in Israel and Bad Mergentheim that and how Bad Mergentheim dignitaries had spoken "with notable courage" about the horrors of the Holocaust and the role of their city.

"Would I have acted differently?"

His "journey to childhood" ended with the thought: "I am sorry, my friends, you welcome me here with such sincere cordiality: If you had been born a few years earlier, wouldn't you stand under the swastika, cheering for the brave soldier, or would you perhaps wear uniforms yourselves and take part in the conquest of Europe? Can anyone assure me that none of you were there? And perhaps, when the possibility came to escape the battlefield and the cold and warm up in a barrack - say, for example, as guardians of transports of people whose fate was already sealed anyway in order to save one's own life - could one resist such an attempt? Would I have acted differently myself if I had gotten into such a situation?"

The legendary Robert Capa

Of course a journalist like Shimshon Ofer did know the name of the famous war photographer Robert Capa. In 1988 the name appeared in a memo. The Tel Aviv Museum announced an exhibition of pictures of the war reporter. "This could be interesting," he said to himself.

Robert Capa had long since become a legend. He had influenced generations of photojournalists. He said, "If your pictures aren't good enough, you weren't close enough. And he was always close: in the Spanish civil war of 1937, when Republicans and leftists fought against the Hitler supported Franco fascists, or on June 6, 1944, during the invasion in French Normandy within the first wave of landings at "Omaha Beach". Once he was too close: On 25 May 1954 he had accompanied a troop of soldiers in the Indochina war, climbed up a hill to take a picture from above. It was his last. He stepped on a mine and was fatally wounded. Almost six years to the day before his death he and Shimshon Ofer had met in Israel - without knowing it.

Capa's photo exhibition in Tel Aviv was organized in 1988 to mark the 40th anniversary of the founding of the state. Shimshon Ofer walked up the steps to the Tel Aviv Museum, upstairs the exhibition hall opened and on the opposite wall was this one picture. It was that smile from the young soldier that attracted him. "I know that smile," he said to himself.

The Discovery

He came closer and with each step he realized what and who he had in front of him. "It's my unit." He remembered the pad, the sand, the face, that smile. He took a closer look and discovered - himself. A tall young man, with his back to the camera, the carabiner over his right shoulder, his sleeves rolled up, a dark shirt and shorts. He was the second last in the right row, behind him only a young man with three mortar grenades in his hand. And... he kept this discovery to himself for the time being.

Only years later, at a meeting with friends in Tel Aviv, he reported about it for the first time. "Well," they said, "you're documented for eternity." A few years later, during a visit to Israel, he gave the author of these lines the historical book from that photo exhibition. Quite casually, as if it were hardly worth mentioning, he mentioned: "By the way, take a closer look at this one photo here". He points to the image of the young men. There was a detailed text in the book. It said: "We all know this photo. It is one of the best-known images of our time. It is sad, heroic and dangerous, although the danger is not here, but behind the horizon". Shimshon said, "Do you recognize anyone in the picture?" - "No, nobody." "That's me" - It lasted a few seconds: "Excuse me?" You are in that photograph of Robert Capa?" "Yes" - "But how...?? Tell me!"

Postscriptum

2018, a few weeks ago on the phone: "Shalom Shimshon, I want to ask you something. I would like to write down and publish the story with you and Capa's photo." "Do you think so? That's nothing special" - "Yes, it is" - "Okay" he said.

Shimson Ofer (89) now lives in Tel Aviv, has one son, one daughter and four grandchildren. Daughter Irit studied physics and mathematics. Today she is a researcher and lecturer in mathematics at a college. His son Eyal also went into journalism as a photographer. In 2004 he published an illustrated book about "The Wall", which since then has separated Israel from the occupied West Bank after countless suicide attacks by Palestinian terrorists.

"Walls are no solution"

He wrote of his own fear of going to a restaurant or a supermarket, "for fear that there is a living bomb next to me". And yet "walls and fences are no solution. If we do not take advantage of the relative calm and limited time the wall is giving to us, we will discover that the wall and fence have given the Israeli side only an illusion of security and demanded a high price, namely that the hate on the Palestinian side became stronger and deeper. The only solution is mutual respect. Sit and talk until you get a result". And finally, he recalled a quotation from Theodor Herzl, the spiritual father of a Jewish state: "If you want, it's not just a fairy tale."

>>> see photo gallery "shalom aleikum"